[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=” av-medium-font-size=” av-small-font-size=” av-mini-font-size=” av_uid=’av-k2mc2byt’ admin_preview_bg=”]

If you haven’t kept up with a regular maintenance schedule, catch up now to avoid the potential legal nightmare that could result if you have a fire and your system doesn’t function the way it should.

“One of the first things your property insurance carrier is going to ask for after a fire is a copy of your inspection, testing and maintenance requirements, and if it turns out you haven’t been maintaining them in the way they’re intended, they could use that as justification for denying a claim,” explains Rob Neale, principal of Integra Code Consultants. “If there’s a tort involved – maybe someone got hurt or was killed and there was a proximate cause related to the fire detection system – there could be legal ramifications.

“If you have a hotel fire, for example, and someone is hurt or killed and the family discovers that you haven’t had the fire alarm system inspected or tested in four or five years, they’re definitely going to go after you for that on a civil matter.”

3 Fire Protection Basics for Commercial Buildings

No matter what type of building you manage, there are three duties that you need to either take care of on a regular basis or bring in a third-party contractor for, Neale says.

1. Inspection

You need to do regular visual checks of each fire detection, notification or protection device and make sure everything is still intact and the unit appears to be in operating condition. This should happen as often as every month if possible, Neale recommends. This task is easy enough for a building owner or facilities department to handle in-house.

2. Testing

A formally qualified tester has to come in and test the equipment to see how it will perform during an emergency. This task is generally farmed out to third-party testing services, Neale says.

3. Maintenance

The manufacturers of each part of the fire protection system will require certain maintenance to keep the various components in good shape. Think of the fire protection system like a new car, Neale suggests: “The first thing you do when you get to the lot is walk around the car, sit in it and look it over. That’s an inspection. Then you take it for a test drive to see how it performs – that’s a test. When you buy it, there’s an owner’s manual in the glove box that tells you how often to change the oil – that’s maintenance.”

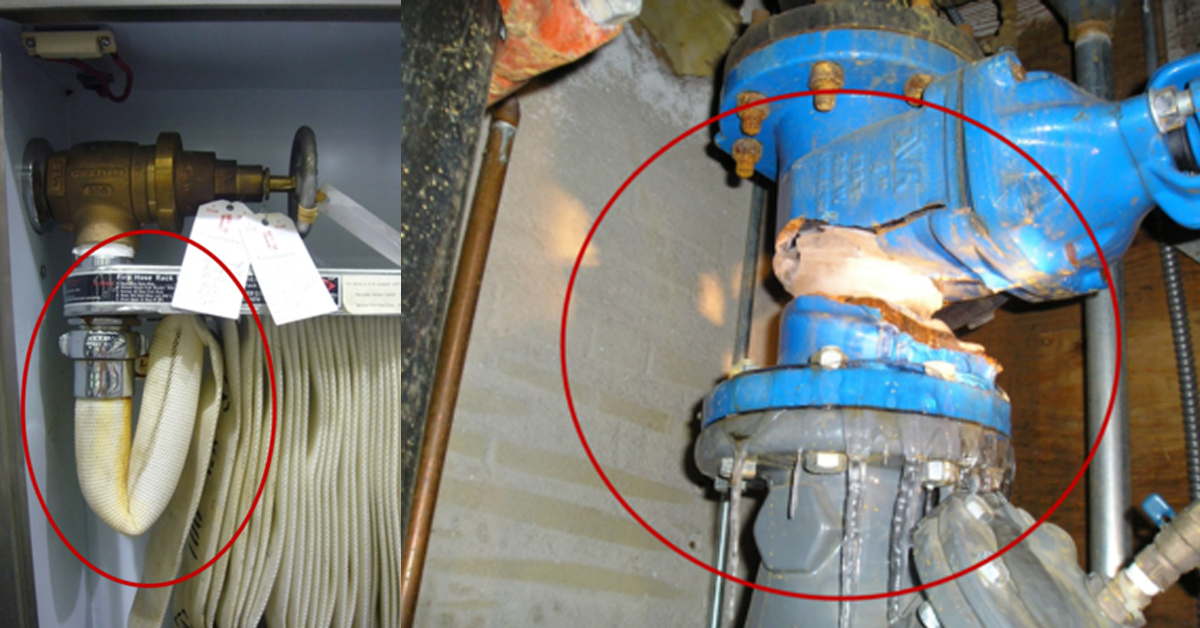

Depending on the type of system and the components, you might have to run pumps weekly and document whether they performed, Neale suggests. You might need to make sure a sprinkler system’s valves are lubricated or even periodically disassembled to check that the system isn’t corroded or blocked. (Pictured: Ice accumulation resulted in a frozen and cracked fire sprinkler control valve. Photo: Integra Code Consultants)

In addition to manufacturer-specific requirements, you’re also bound by local codes and standards, explains Rodger Reiswig, vice president of industry relations for Johnson Controls. Local requirements are often based on either the International Fire Code (IFC) or codes issued by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA).

Find out what your municipality or state has adopted (and which version) and use that to inform your inspection, testing and maintenance schedule.

You’ll likely need to become familiar with NFPA 72, which covers installation, testing and maintenance of fire alarm and signaling systems, as well as NFPA 101 (the life safety code) and NFPA 1 (the fire code). Your local authority may also have declined to adopt certain parts of the code or added local requirements based on geography or other factors, Reiswig says, so it pays to find out exactly what the local version is and follow that to the letter.

At minimum, Reiswig says that every device and the control unit components need to be inspected at least once a year, or even semi-annual or quarterly.

“The other thing to know is that codes come out every three years and some jurisdictions might be under an older version of the code,” he says. “Something that has changed in the codes is secondary power requirements, a lot of which is now governed by NFPA 110. If you have an engine-driven generator, you need to make sure that backup power is inspected monthly.”

The alarm system should be tested roughly every six months to make sure that it activates properly, adds Robert Solomon, division director (building/life safety codes and systems) for NFPA.

“That test will involve everything from simply making sure that the device is functional, operational and not obstructed to making sure that the proper activation of the building fire alarm system occurs once they pull the lever,” Solomon says. “That brings in another phase of what people are looking for. Are the horns and bells working at an appropriate decibel level? Are the strobes activating properly? If the system is connected to a central station, is the signal going through the central station or directly to the fire department?”

Special Requirements for Building Fire Protection

Some building types require specialized equipment depending on who uses the facility, Neale notes. “In a school, you typically have a very controlled environment. The teacher is in charge of the students and they train with fire drills and evacuation, so if there’s a problem, they can generally leave on their own,” Neale explains.

“Health care facilities have more restrictive rules because people in there can’t just get up and walk out. If you’re in the operating room or the ICU and the alarm goes off, you’re not leaving without some help,” he says. “That’s why those types of facilities have more restrictive requirements in terms of fire protection systems, fire separation, smoke control and ways to protect the person – what we call ‘defend in place’ rather than trying to evacuate.”

Requirements for office buildings are typically straightforward because, in theory, people working in an office are awake, alert, oriented, can respond quickly in an emergency and can self-evacuate. A high-rise office building will typically have speakers rather than the horns you’d find in a shorter building, Neale adds. “When I go to a 10-story office building, I know it’s going to have a voice fire alarm system and it’s playing messages to get instructions to people rather than just beeping. That also means there’s more maintenance required for the amplifier. Also in a high rise, I’m required to have firefighter telephones or a bidirectional amplifier and repeater.”

Those instructions are typically targeted to whatever floor the fire is on and the floors above and below it to avoid a stampede of every floor trying to evacuate at once, Solomon mentions.

“Let’s say I’m in a 50-story high-rise building and I have a fire alarm activation on the 37th floor. Instead of sending a signal to all 50 floors of the building, I can send a very specific alarm with a follow-up message to people on the 37th floor, where the alarm originated, and the floors above and below, floors 36 and 38,” Solomon explains. “Instead of trying to empty a 50-story building, we’re going to initiate the alarm on three floors. After it gets attention, the announcement will come on saying there’s been a fire reported on the 37th floor and direct occupants on 36, 37 and 38 to either relocate to a lower level or leave the building. There are options that the NFPA codes and standards would allow.”

In addition to influencing the installation requirements, occupancy and building type also influence testing, Neale adds. It’s optimal to conduct the testing when no one is in the building – for example, nights or weekends – but that’s probably impossible if you’re managing a hospital.

If your building is always occupied, work with the inspection company to conduct the tests in phases and move people out of the testing areas as much as you can.

“There’s no requirement that everything has to be done at the same time, so we could write a contract that says I’ll inspect 50 percent of the system in January and 50 percent in July. In a very large facility, they might do quarterly inspections with 25 percent of the system at once,” Neale says. “The advantages of that are that you’re having an expert come in and look at your system every three months. Some people are under the impression that you’ve got to do everything in one shot. Talk to the fire alarm contractor and don’t be afraid to ask those kinds of questions.”

3 Tips for Fire Protection System Optimization

Meeting the bare minimum required by the International Fire Code or the applicable NFPA codes will make sure that you stay in compliance, but that’s all. Going beyond the code requirements in some areas can help you maintain a safer building with fewer headaches.

Consider these ideas for making sure your fire protection system is fully maintained, code-compliant and ready to deploy at a moment’s notice.

1) Make more than one copy of your documentation.

Aside from the mandatory inspection, testing and maintenance routine, you need proof that you’ve actually been doing what you’re required to do.

Document every interaction you have with your fire protection system, even the simple visual inspection where you simply look at the unit and confirm that no one has vandalized it recently. The records must be readily available to the authority having jurisdiction (AHJ) over your area.

“If you want to keep everything in a single location in your desk drawer, that needs to meet minimum requirements,” Solomon states.

A good practice is to keep a physical set in the office they work in and another set in a companion building at a different location. Another trend is keeping a set of records in the cloud. If the building gets wiped out by a fire, earthquake or tornado you can still have access to them, he says.

“The requirement NFPA has is that whenever the AHJ comes in, the inspection, testing and maintenance records have to be readily available. If you can reach in your desk drawer and say, ‘Here are the reports for last year,’ that meets our requirements. If you give the AHJ a login to go look at reports in the cloud, that also meets our requirements.”

If you use a third-party service for testing and maintenance, review their records periodically to make sure they’re documenting everything they’re supposed to, Reiswig adds.

2) Install extra detection.

You can go above and beyond with installing extra equipment as long as all of it meets minimum requirements, Reiswig says.

(Pictured: This smoke detector is covered with a rubber glove, a glaring (and easily fixable) violation. Photo: Johnson Controls)

“People often do that because there’s a certain floor or area where they store important things. If there’s even an inkling of a fire, you might want smoke detectors in some areas that don’t require them,” Reiswig explains. “But you’ve got to be careful with the codes because the codes say if you put in voluntary equipment, it all has to conform to the code. If you want to put smoke detectors in the corner of your warehouse because you keep important stuff over there, you can do that, but you have to install them in the whole space.”

3) Upgrade to better equipment.

The voice alarm for a high-rise building can provide extra value if it also incorporates a mass notification system, adds Solomon. The voice component is mandatory but a mass notification system could deploy messages in multiple formats so that people who can’t hear the voice alarm can also receive the instructions.

Some systems can capture computer screens or send out automated texts or phone calls to make sure everyone who needs to receive the message is able to get it. “That’s going to cost more money, but the building owner might say ‘It’s worth the extra investment for safety and I’m willing to pay for enhanced features,’” Solomon says.

10 Ways Your Fire Protection System Might Violate Code

These pitfalls are fairly common, but they can interfere with your fire protection system’s ability to do what it was designed to do – protect your building and its occupants during a fire. (Pictured: Combustible dust has accumulated on this dryer exhaust vent. Photo: Integra Code Consultants)

Do any of these sound familiar?

1) Duct smoke detectors in air handlers.

This is one area that Rodger Reiswig, vice president of industry relations for Johnson Controls, sees can become an issue if it’s not inspected or maintained properly.

When dust accumulates on an electric fan motor like this,

a spark or heat from the motor could easily ignite it.

“A lot of our customers have big air handling units that are required to have smoke detectors in the duct system that detect smoke from the fans, filters and motors,” he says. “As you can imagine, there’s a lot of air moving and if filters aren’t changed properly, dust and dirt can contaminate these devices pretty quickly. They’re usually up high, concealed and hard to get to, and sometimes the person they hired might not be able to do due diligence. If someone says ‘I tested everything else but I couldn’t get to your duct detectors,’ find somebody else.”

2) Blocked pull stations.

Manual alarm pull stations are common in hospitality venues and are frequently blocked by planters or racks of brochures, Reiswig says. “Sometimes people will block them without realizing they’re doing it. They’ll put a banner or a flyer right over top of the lever to tell people there’s an event.” (Pictured: This strobe is hidden behind a plant where it can’t be seen easily during an emergency. Photo: Johnson Controls)

3) Air diffusers that are too close to smoke detectors.

This commonly crops up after an HVAC renovation changes the diffusers’ original location, Reiswig explains. If they’re too close to smoke detectors, they’ll blow dust and dirt right onto the detector and contaminate it, which can result in false alarms.

4) Only part of the fire protection system is inspected.

Find out exactly what your contractor is and isn’t testing, because the regular protocol may only include part of your fire protection system. Many owners own a sprinkler system from one vendor and a detection and alarm system from another, and not clarifying who is responsible for testing what may lead to a partially untested system or a disagreement between vendors over who is supposed to test which components.

“When you get your contract proposal from the inspection company, ask if there’s anything in the system they won’t be testing. You should know that up front,” Reiswig says.

5) Dead batteries.

Older control units often have a battery backup. Even if you also have generators for redundancy, if batteries are an option, you need to replace them.

6) Blocked exits.

(Pictured: Never use the fire stairs for storage. During an emergency, these boxes will slow or stop people from trying to evacuate. Photo: Integra Code Consultants)

“Keeping the exits clear and open is a fundamental thing,” says Robert Solomon, division director (building/life safety codes and systems) for the National Fire Protection Association. “In restaurants, it seems like a lot of times there will be a table and chairs right in front of the secondary exit door or you’ll go into a big box store and they’ll be restocking and have the forklift parked in front of one of the many exit doors along the perimeter wall.

“Even in an office building, I’ve seen contractors pull up in front of our building and try to stage the sheet rock in the exit stair. I understand it’s only going to be there for 30 to 45 minutes, but the codes are very strict about not using those exit stair enclosures for storage of anything.”

This exit stair is almost impossible to navigate around. Imagine a crowd of frightened occupants trying to evacuate through this stairway during an emergency. The stored items are combustible and the remaining pathway is smaller than the required 36 inches. (Photo: Integra Code Consultants)

7) Not testing generators and pumps well enough.

Owners tend to assume that if the generator or pump starts and runs successfully for a few minutes, it’s good to go.

“Our test protocols want the engine to start, run and make sure it’s running long enough to come up to operating temperature, but on an annual basis we also want to make sure everything is working, so we have a requirement for you to discharge water at the rate of capacity of the fire pump,” Solomon says. “What we’re doing there is making sure it’s still performing the way it was intended. If the flow isn’t what it should be, that could be evidence of a closed or partially closed valve upstream. With the generator, you want to make sure it’s providing the appropriate power output to the emergency systems.”

8) Compromising fire doors.

“Fire doors are designed to create a barrier between various parts of a building, so if part of it catches on fire, the door closes automatically and protects the rest of the space,” Neale explains. “The trouble with fire doors is that they’re inconvenient because every time you go through it, it closes behind you, so people prop them open.” (Pictured: This hotel has a fire door propped open. If there’s a fire, it will spread faster and more easily through open doorways. Photo: Integra Code Consultants)

9) Neglected exit signs.

“A lot of buildings have exit signs that perform the function of both lighting the sign and downlighting the exit path and those burn out fairly regularly,” Neale says. “Those often get overlooked because people say they’ll get around to it eventually.”

10) Overtaxed electrical equipment.

Daisy-chained power strips are extremely common and can lead to fires by overheating electrical outlets, Neale says. (Overloaded plugs are a fire waiting to happen. This setup daisy-chains multiple power strips increases the risk of overheated wiring that can lead to a fire.

Resources:

NFPA (nfpa.org): The National Fire Protection Association has developed more than 300 codes and standards covering every aspect of fire and other safety risks. View any of the codes for free online or order a hard copy.

ICC (iccsafe.org): The International Code Council develops the International Fire Code. Order a copy of the code itself or make it easier to manage your fire protection system with the Fire Inspector’s Guide or Fire Code Essentials.

OSHA (osha.gov): OSHA includes fire safety guidance among its other occupational health and safety resources.

Contact M&M Fire Protection & Security (574) 533-8111

[/av_textblock]